3.3 Hamida Begum v Maran

Hamida Begum v Maran(1)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev 1) [2020] EWHC 1846 (QB); Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326. is a newly decided case by the English Courts which discusses some of the possible grounds for establishing a duty of care owed by a former ship agent vis-à-vis a shipyard worker.

The Claimants also included a claim for unjust enrichment available under English law. This claim was held unsustainable by the High Court(2)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev 1) [2020] EWHC 1846 (QB) paragraphs 73–74, 98. The decision that the claim of unjust enrichment would be unsustainable was not appealed. and will not be of further relevance to include in the analysis of the duty of care.

Another question for the courts was whether Bangladeshi law should apply, as this would entail a one-year limitation period, and thus the claim would be statute barred. This issue is solely included briefly to have the full picture of the case but is not part of the analysis as the present thesis aims at assessing the nature of the duty of care rather than the choice of jurisdiction.

3.3.1 Facts of the case

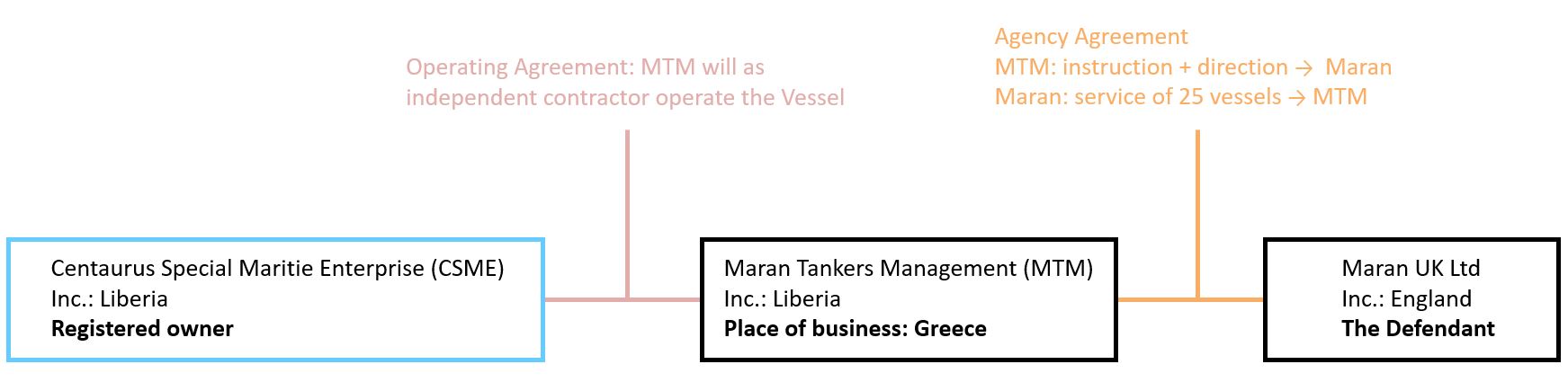

Mohammad Khalil Mollah (hereinafter referred to as “the Deceased”) worked on the demolition of the oil tanker MARAN CENTAURUS (hereinafter referred to as “the Vessel”) in the Zuma Enterprise Shipyard (hereinafter referred to as “the Yard”).(3) The Deceased’s employer was not known, cf. Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev 1) [2020] EWHC 1846 (QB) paragraph 11. On March 30th, 2018, he unfortunately fell to his death working on the Vessel. This led his wife, Hamida Begum (hereinafter referred to as “the Claimant”(4) “the Respondent” when referring to the appealed case.), to claim damages for negligence against Maran UK Ltd (hereinafter referred to as “the Defendant”(5) “the Appellant” when referring to the appealed case.). The Defendant was the former ship agent of the Vessel which the Deceased had been working on when he fell to his death. Thus, the Defendant was not the owner of the Vessel, but had an agency agreement with MTM, who had an operating agreement with CSME. CSME was the registered owner of the Vessel (see Figure 1 below). Interestingly, the case therefore also involves the question of whether the ship agent would not be liable, as they were not the actual owner of the Vessel.

Figure 1

A full overview of all known parties involved is presented in Annex A under paragraph 6.

The Claimant claimed damages against the Defendant based on two “routes”, creating an alleged duty of care owed by the Defendant vis-à-vis the Claimant. The first being that the Defendant owed a duty of care based on the basic duty of care notion established in Donoghue v Stevenson.(6) The first route relates to the neighbourhood principle as laid down under paragraph 3.2.1.1 above. The second route was that the Defendant owed a duty of care towards the Claimant because the Defendant had created a state of danger which a third party exploited.(7) The second route is thus one related to liability for omissions as laid down on paragraph 3.2.2 above.

On February 28th, 2020, the Defendant filed an application notice to strike out the claim and alternatively for a summary judgement. Both are English law remedies, where the court is able to “throw out” the case. If the court renders that there are no reasonable grounds for bringing the claim, the court can thus decide to strike it out. The summary judgement remedy will allow the court to find in favour of the Defendant based on the limited facts presented if it finds that the claimant has no real prospect of succeeding on the claim, i.e. that the claim is bound to fail.(8)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev 1) [2020] EWHC 1846 (QB) paragraph 5; Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraph 20. A realistic claim entails that the claim is not fanciful and carries some degree of conviction. This includes a test of whether the claim is bound to fail.(9)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraph 22.

Justice Jay in the High Court held that the Claimant had a real prospect of succeeding in relation to her claim in negligence and thus dismissed the application for summary judgement as well as to strike out the claim.(10)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev 1) [2020] EWHC 1846 (QB) paragraphs 98–99. Even though the judge held that Bangladeshi law would apply and thus that the claim would be statute barred, the Claimant had a prospect of arguing the application of Articles 7 and 26 of the Rome II convention, which would circumvent the one-year limitation period under Bangladeshi law, which had not been complied with.

The Defendant appealed the decision by the High Court. On March 20th, 2021, the Appellate Court upheld the High Court’s decision to dismiss the application for summary judgement as well as to strike out the claim.(11)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraphs 72, 116. The Appellate Court reiterated the conclusions made by the High Court and well-established principles that in novel and fast developing areas of the law, a decision should not be made upon hypothetical (and possibly wrong) assumptions but on actual findings of facts. The reluctance to strike out cases in these areas are argued also to be because of the European Court of Human Rights’ criticism of the procedure.(12) Van Dam, above no 49, 84.

Thus, the case is now awaiting trial, but it is relevant and interesting to examine the grounds on which the courts decided to dismiss the motion to strike out the claim and/or give a summary judgement. Even though these grounds and findings may be disputed at trial, one can argue that the court may be somewhat inclined to at least take the considerations made by the High Court and Appellate Court into consideration, as they are more than simple findings in one ship recycling case. They are another indication of the tendency in the courts to allow liability for companies where their acts and omissions contribute to or engage in unsafe and non-environmentally friendly practices. There is a tendency to impose liability on the ultimately stronger party because of their ability to carry this liability and perhaps also their knowledge, which they can no longer claim to be unaware of, given technological developments.(13) Even states are imposed liability in this regard. See for instance the Dutch case, where the Dutch state was held accountable and imposed a duty to take action to reduce the green house gas emissions, ECLI:NL:GHDHA:2018:2610 C/09/456689 / HA ZA 13-1396 (English translation); This can be compared to the argument in supply chain liability cases, where the parent company is found to have superior knowledge and thus better suited to carry the liability, see Rott and Ulfbeck, ‘Supply Chain Liability of Multinational Corporations?’, 234. One may find support in the business literature for this position, i.e. that corporations’ economic and political power “increasingly makes them subject to expectations to assume social responsibility or legal liability”(14) Buhmann and Wettstein, ‘Business and Human Rights’, 5..

With a summary judgement as the one in the present case, no mini-trial is conducted, and thus the courts are bound to make certain assumptions of the facts based on the parties’ submissions. These assumptions will thus be examined in the following paragraph.

3.3.1.1 Factual assumptions

Given that the case was an interim decision, not all factual findings and discovery were made at trial. Thus, the Courts had to make factual assumptions, on which to base their conclusions. When deciding the case in this regard, the Courts had to do so on the basis of the Claimant’s best case on the law.(15)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev 1) [2020] EWHC 1846 (QB) paragraph 36; Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraph 36. This also meant that the Courts would not conduct a mini-trial, but accepted the Claimant’s arguments unless its factual assertions were demonstrably unsupportable. This included considering that further facts would appear at trial.(16)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraph 22.

The Appellate Court decided it was instructive to summarise the factual assumptions into eight assumptions instead of having them throughout the judgement as done by the High Court.(17) Ibid., paragraph 21. Thus, the following section will present the assumptions, as done by the Appellate Court, with inclusion and reference to the remarks of the High Court.

Firstly, it was evident that the Vessel needed to be scrapped and that oil tankers of the size of the Vessel are hard to dispose of safely.(18)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev 1) [2020] EWHC 1846 (QB) paragraph 30; Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraph 27.

Secondly, the Defendant had a choice as to whether it would sell the Vessel to a party ensuring a safe disposal or not.(19)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev 1) [2020] EWHC 1846 (QB) paragraph 30; Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraph 28; Thus, by taking the supply chain liability considerations into account, one may argue that the choice of a shipyard with low environmental and safety standards the seller ‘outsources’ and thus have a superior knowledge, see Rott and Ulfbeck, ‘Supply Chain Liability of Multinational Corporations?’

Thirdly, the Defendant had complete autonomy over the sale of the Vessel. Justice Jay found that the position of the Defendant was probably legally indistinguishable from that of MTM (the operating agent) as well as CSME (the registered owner). The Defendant agreed to view control at its highest and thus assume that the Defendant had autonomy over the sale and therefore also accepted that “the commercial realities went further than the four corners of the contract”(20)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev 1) [2020] EWHC 1846 (QB) paragraph 19.. In addition, Justice Jay found that there was “a real prospect that an examination of the complete evidential picture at any trial would support the high watermark of the claimant’s case on control”(21) Ibid., paragraph 19..

Fourthly, the Defendant knew that the Vessel would be broken up in Bangladesh due to two main facts. The first being the high price, and secondly the low amount of fuel left. The Defendant accepted that it “was aware of the ultimate destination of the vessel”(22) Ibid., paragraph 14.. Assessing the amount of fuel left is relevant in regards to assessing the Defendant’s knowledge of where the Vessel would be broken up as the amount taken together with the position at the time of the sale (Singapore) and the size of the Vessel only left one other safe option possible, namely in China. However, due to the high price of the Vessel, the costs of breaking the Vessel up would entail that China could not be viewed as possible anyway.(23) As noted by Justice Jay, only 80,000 tonnnes out of the nearly 11 million tonnes broken up in 2018 where broken up in Chinese and Turkish yards, cf. Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev 1) [2020] EWHC 1846 (QB) paragraph 15. Thus, the inference that an amount of low fuel left and a high price would create the necessary grounds to establish knowledge of the end destination for recycling by the Defendant seems justified. In the absence of any evidence to the contrary, Justice Jay agreed to the inference that the high price and low amount of fuel would mean that the Defendant knew that the Vessel was to be broken up in Bangladesh.(24) Ibid., paragraphs 14, 30. According to Lord Justice Males, the price and fuel showed knowledge of and intent to send the Vessel to Bangladesh, which was equal to the same control as if the Vessel had been sold directly to the shipyard.(25)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraph 127.

Fifthly, the Defendant accepted (for the application only) that beaching is “an inherently dangerous working practice”(26)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev 1) [2020] EWHC 1846 (QB) paragraphs 13, 30; That the practice used for ship recycling is of low human and environmental standard also appear from the EU Ship Recycling Regulation, according to which the purpose of the regulation was (and is) to redirect the practice from the substandard sites which is currently the practice, see Regulation (EU) No 1257/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 November 2013 on ship recycling and amending Regulation (EC) No 1013/2006 and Directive 2009/16/ECText with EEA relevance, 7 preamble..

Sixthly, since the Defendant chose to sell the Vessel to a buyer who would not meet safe demolishing practices, it exposed workers like the Deceased to “a real risk of death or personal injury”(27)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraph 32..(28)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev 1) [2020] EWHC 1846 (QB) paragraph 56.

Seventhly, in regard to the risk, Justice Jay held that it was only foreseeable that the Deceased would sustain a serious accident even though the exposure to the risk of personal injury was inevitable. However, he then went on to assume that the Deceased’s accident was probable and thus a foreseeable risk.(29)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev 1) [2020] EWHC 1846 (QB) paragraphs 42–43; Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraph 33. As stated under paragraph 3.2.2 with reference to Smith v Littlewoods(30)Maloco v Littlewoods Organisation Ltd [1987] UKHL 3., probability is enough to meet the foreseeability requirement.(31) Ibid.; Jones M A et al., Ibid., paras 8–55. As put in Home Office v Dorset Yacht(32)Home Office v Dorset Yacht Co Ltd [1970] UKHL 2., it would be likely(33) Ibid., paragraphs 1029, 1033. that the Deceased would be exposed to the fatal injury, which would be enough for foreseeability to be met. Lord Justice Males in the Appellate Court characterised the damage as “entirely foreseeable”(34)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraph 122. and that it was a certainty.(35) Ibid., paragraph 124.

Eighthly, the intervention by Hsjear (the cash buyer) did not alter the Vessel in any way.(36)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev 1) [2020] EWHC 1846 (QB) paragraph 37; Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraph 34. Without too much reiteration, the same argument cannot be said to be found in Lord Justice Males’ argument under the fourth assumption.(37)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraph 127. Thus, one may not regard the selling to a cash buyer as a novus actus which would otherwise break the chain of causation.

3.3.2 Decision by the Courts

The following section will introduce and analyse the findings of the High Court and Appellate Court (hereinafter referred to as “the Courts”) based on the assumptions set out above. It will do so by firstly looking at the first route claimed to have created a duty of care owed by the Defendant towards the Claimant, namely the one established in Donoghue v Stevenson(38)Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] UKHL 100.. Hereafter, the second route argued by the Claimant will be examined. Here, the Claimant argued that the Defendant owed a duty of care based on the principle that the Defendant was responsible for a state of danger that was exploited by a third party.(39) This exception was stated to only be applied in very rare situations, cf. Maloco v Littlewoods Organisation Ltd [1987] UKHL 3 paragraph 273

3.3.2.1 Duty of care (Route 1)

When assessing whether the Defendant owed the Claimant a duty of care based on Donoghue v Stevenson(40)Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] UKHL 100., the Courts assessed whether the Defendant could reasonably foresee if their act or omission would be likely to injure the Claimant as their neighbour. As recalled from paragraph 3.2.1.1, this requires two elements, namely a special relationship between the Claimant and Defendant and as that the likely damage was foreseeable.(41) Even though, the case was argued on the Donoghue v Stevensen principles, the third criteria of that it must be fair, just and reasonable will apply to any duty of care.

Justice Jay did not see the case as a classic Donoghue v Stevenson. The main reason being the intervention of the Yard or the Deceased’s employer, which was in contrast to Donoghue v Stevenson, where no intervening act(s) by any third party in the chain of contractual relationships occurred.(42)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev 1) [2020] EWHC 1846 (QB) paragraph 37.

In the Appellate Court’s review, they commented on the fact that the Respondent(43) As the Claimant in the High Court did not appeal the decision, they are the Respondent, where the Defendant is the Appellant in the Appellate Court’s decision. put great weight on the requirement of foreseeability as if this would be able to create the duty of care alone.(44)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraphs 40–41. However, the fulfilment of this requirement would not be enough, as especially for novel areas of the law, the full three-stage test(45)Caparo Industries Plc v Dickman [1990] UKHL 2. must be applied.(46) Jones M A et al., above no 49., paragraph 8–25. Even though the tendency towards imposing liability in these novel areas of law, where companies outsource their business or similar on the grounds of the fairness criteria, the same criteria is the one being used for dismissing such liability. In particular, the floodgate argument is here being used to create some barrier from liability to be imposed.(47) The floodgate argument was the basis for rejecting the claim of the injured workers at the Rana Plaza factory incident in Bangladesh, see Das v. George Weston Limited 2017 ONSC 4129 paragraph 452. One may consider whether this is truly fair. With the ability to outsource or choose a cheaper contractor someplace else, where legal justice and law enforcement may not provide the same protection, one could argue comes a responsibility not to take advantage of this gap. A gap, which by some scholars is described as an imbalance in trade and human rights created because of the very same freedom of trade.(48) Van Dam, above no 9, 226. The floodgate argument can also be used in support of the proximity criteria as a condition, as the absence of such a relationship would indeed create an enormous amount of claims of which at least some would also be unforeseeable.

In addition, the Appellate Court, with all fairness, posed the question of whether a shipbroker in London ought to regard a worker in a Bangladeshi shipyard as their neighbour, for which an affirmative answer would entail the neighbour criteria to be met.(49)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraph 41.In answering this, one may look to the speech of Lord Atkin in Donoughue v Stevenson, where he said that “The answer seems to be persons who are so closely and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have them in contemplation as being so affected when I am directing my mind to the acts or omissions which are called in question.”(50)Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] UKHL 100 paragraph 580.

Thus, one may argue that even though there is quite some (physical) distance between a shipbroker in London and a worker in Bangladesh, the high price and low amount of fuel indicated that the Defendant would have known whereto the Vessel would be sent in the end. Knowing this destination, the Defendant would also know the risks associated herewith as the reputation of the shipyards in the third-world countries are no secret. It is, and especially for a shipowner(51) It is argued by some scholars that this knowledge is known to all parties in the business, including the insurance companies, etc. and thus they ought also to take a responsibility to ensure the unsafe and non-environmentally safe practices of ship recycling be stopped, see Klevstrand, ‘Jusprofessor Om «Harrier»-Saken’., reasonably known that vessels are dismantled in a non-environmentally friendly and unsafe way in these places. Thus the Defendant ought reasonably to have had in contemplation the shipyard workers when choosing to sell the Vessel at the given price and fuel level left. Arguably, it will be hard to establish that the Defendant knew nothing of the recycling destination and practice and thus the inference that the Yard workers would be neighbours of the Defendant would be met.

The Respondent argued that the requirement of proximity between the parties ought to be answered by way of two questions. The first being that if the Appellant had sold a dangerous product to the yard with full knowledge of the yard’s dangerous practices, would the relationship between the Deceased and Appellant then be sufficiently approximate? The Respondent answered this affirmatively. The second question was then whether such duty could be negated as a result of the intervention of a third party, which was answered negatively.(52)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraph 42. Thus, according to the Respondent, the requirement of proximity would be met.

However, one may argue that in Donoghue v Stevenson the product, a ginger beer with a rotten snail, was a dangerous product in itself, which the Vessel wasn’t. Thus, when the Respondent argued that it was the dismantling, which was dangerous, the Appellate Court argued that this would take the case outside the scope of Donoghue v Stevenson, because it then did not concern an inherently dangerous product as such.(53) Ibid., paragraph 43. Against this argument, one may recall the Basel Convention, which includes end-of-life ships as hazardous waste under paragraph 2.2.1.(54) UNEP, Decision VII/26. Environmentally sound management of ship dismantling. Thus, one may argue that since ships are considered hazardous waste under the legal regime, ships are also inherently dangerous and thus a dangerous product in itself, which could render Donoghue v Stevenson applicable to some extent.

Even though the case was held not to fit comfortably within the principles laid down in Donoghue v Stevenson, the Appellate Court agreed with the High Court that it was not so fanciful that it should be struck out, and the second route of arguments strengthened the Appellate Court’s view in this regard.(55)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraphs 49–50. The second route relating to a duty of care for omissions will therefore be analysed in the below paragraph.

3.3.2.2 Duty of care (Route 2)

The following section will introduce and assess the Courts’ findings in regard to the Claimant’s second route, namely that the Defendant owed a duty of care toward the Claimant because it had created a state of danger, which a third party exploited. This is therefore an argument that the Defendant is liable for its omission to act to avoid such harm, and thus one of the exceptions to the general rule that no liability is imposed for omissions. That is for in cases where one party must bear a specific responsibility for protecting the other from harm caused by third parties. This is however not a general rule and can only be said to happen in rare circumstances such as the four listed above in paragraph 3.2.2.

In assessing the applicability of the exceptions to the general rule that there is no liability for omissions, both the High Court and Appellate Court(56) The Appellate Court further noticed that the analysis by Justice Jay in the High Court was somewhat hard to follow, partly also because the case does not easily fit within a recognised liability category, see Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraph 17. had some difficulties. This was because the exceptions are only relevant to so-called pure omissions, and Begum v Maran could be identified as a mix of acts and omissions. Justice Jay proceeded on the basis that the case ought to be viewed as a hybrid and made notice of the fact that the case distinguishes itself from other omission cases where liability has been assessed when damage has been caused by third parties. Namely, in Begum v Maran, the immediate lack of proximity between the Defendant and the Yard/employer as there was no control over or responsibility for the potentially dangerous situation from the Defendant.(57)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraph 45. Thus, one may argue that the control exercised by the Defendant over the cash buyer, which went beyond the four corners of the contract(58)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev 1) [2020] EWHC 1846 (QB) paragraph 19., would be hard to argue to have created control over the Yard also. Even though the Defendant knew where the Vessel would be destined and that the practices here would be unsafe, the only control it would have would be not to sell the Vessel at the given price or make sure that safe recycling practices in the sales contract would be followed by the cash buyer. Thus, this control would hardly be categorised as control over the Yard’s working conditions, which was prima facie the reason for the accident that led to the death of the Claimant’s late husband. Given the rapid developments in the courts in this area of law, one could perhaps cautiously argue that the choice of not selling it to the given buyer, a lower price, or similar, would also be some kind of control because this would entail that the Yard’s with lowest safety measures would gain less and less work. Thus, this would maybe force them to actually improve their sites, and ultimately this could perhaps be some sort of indirect control. Only time can tell.

The Appellate Court seems to have found a more elegant route by way of highlighting that pure omissions may be regarded as a somewhat outdated term. Even though this was the case in Smith v Littlewoods(59)Maloco v Littlewoods Organisation Ltd [1987] UKHL 3., in which the principle of no liability for omission was set out, later authorities imply that liability arising from the intervention of third parties may be conferred differently nowadays. Here, the Appellate Court referred to Lord Reed’s distinction in Poole, where Lord Reed made a distinction between causing harm (making things worse) and to confer a benefit (not making things better).(60)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraph 60. It is in the latter situations that the courts are reluctant to impose a duty. Additionally, the Appellate Court highlighted a line of authorities to the general rule that there is no liability for harm caused by the intervention of third parties and emphasised that these authorities show the rapid speed with which the area of law develops as well as it being one of the most developing ones.(61) Ibid., paragraph 61.

Returning to the High Court’s decision, Justice Jay had, as above stated, come to the conclusion that the case may be assessed as a hybrid of acts and omissions, and he proceeded to discuss the situations in which a Defendant may be liable for omissions.(62) As recalled these exceptions are three, see paragraph 3.2.2.1. Justice Jay dismissed the first, i.e. that there was no assumption of responsibility between the parties. In this regard, he commented that this kind of liability relies on the antecedent relationship between the parties, which was not present between the Defendant and the Yard/employer.

The second exception that control can amount to a duty of care was also not found present. As opposed to Home Office v Dorset Yacht(63)Home Office v Dorset Yacht Co Ltd [1970] UKHL 2., Justice Jay held that the Defendant had no control over the Yard/employer because there was no physical connection between the defendant and Bangladesh, nor could the Yard be regarded as part of the shipping group, who owned and sold the Vessel (the Angelicoussis Group). The latter could also not be established by way of tacit understandings between the Defendant and the Yard/employer. Lastly, the Justice held that control could not be inferred from the fact that the Defendant knew that the vessel had to be disposed of safely.(64)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev 1) [2020] EWHC 1846 (QB) paragraph 48. For a discussion on control, reference is made to the second paragraph under paragraph 3.3.2.1.

However, the third exception was analysed more in depth by Justice Jay, as the question of whether the Defendant could be argued to have created a state of danger exploited by a third party was arguable. In this regard, the Justice dismissed the Defendant’s argument that the Vessel itself was inherently unsafe, but rather it was the working conditions of the Yard which were unsafe. Justice Jay did so by inference that if the Defendant would be liable if the Deceased had died from asbestos, then you could not separate the safety of the vessel from that of the working conditions, and inter alia would liability for asbestos also mean that of the unsafe working conditions. In other words, the danger created by the asbestos would be equal to those of the dismantling of the ship. Thus, the ship could not be regarded as safe in one way and then unsafe if not dismantled safely.(65) Ibid., paragraph 57. The manager and operator of an oil tanker would therefore be regarded as having created the source of danger.(66) Ibid., paragraph 60. In addition, Justice Jay stated that it would be artificial to conclude that the danger was created by the Yard/employer solely. It was a danger inherent in the vessel once broken up. This conclusion also aligns with the previous argument that end-of-life vessels are considered hazardous waste according to the Basel Convention(67) UNEP, Decision VII/26. Environmentally sound management of ship dismantling. as stated under paragraph 2.2.1., and therefore ought also to be considered inherently dangerous.

In assessing the requirement of fairness, justice and reasonableness, Justice Jay even added that the balancing of the arguments in this regard possibly ought to be done in a way “slightly stretching the boundaries of established norms”.(68)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev 1) [2020] EWHC 1846 (QB) paragraph 63. Thus, this arguably represents the tendency seen in relation to the duty of care in general. Indeed, it would not be appropriate to assess this in a simple summary judgement. One may argue that the mentioning by the High Court in this paragraph as well as by the Appellate Court, of all the factors regarding safety, health and environmental issues in relation to the practice of ship recycling, greater weight must be put to those who suffer from others’ exploitation of their stronger position. Here, the Appellate Court made a note of the evidence “that, despite international concern registered in many ways over many years, the dangerous working practices in the Bangladesh shipbreaking yards inevitably cause shockingly high rates of death and serious injuries”.(69)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraph 12. This is also what has been confirmed by various international organisations, such as the World Labour Organisation and the Global Trade Union IndustriAll amongst others.(70) ‘The Toxic Tide’; Ship recycling: reducing human and environmental impacts, above no 5, 3; ‘SPECIAL REPORT’.

Lastly, the Justice referred to the fact that in novel areas of the law and where it is not possible to give a certain answer, it is not appropriate to strike out the claim. Instead, the claim must be decided on its facts.(71)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev 1) [2020] EWHC 1846 (QB) paragraph 64; The Appellate Court agreed with Justice Jay in making this conclusion and the authorities used, see Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraphs 23, 71. The same was also relied upon in Vedanta Resources PLC & Another v Lungowe & Others(72)Lungowe & Ors v Vedanta Resources Plc & Anor [2017] EWCA Civ 1528 (13 October 2017)., which evolved around the parent company’s duty of care towards the mineworkers rather than the company responsible for the day-to-day activities.(73)Vedanta Resources PLC & Anor v Lungowe & Ors [2019] UKSC 20 paragraph 48. Again, the reluctance may also be due to the criticism of the procedure brought forward by the European Courts of Human Rights.(74) Van Dam, above no 49, 84.

Thus, the Claimant was held to have “a real prospect of succeeding in relation to her claim in negligence”(75)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev 1) [2020] EWHC 1846 (QB) paragraph 98., and the application for summary judgement and to strike out the claim was dismissed.

As to the standard of diligence of the Defendant, in relation also to commercial realities, the Justice held that fuel, as well as the purchase price, would be factors to ensure safe recycling, and that indeed a contractual structure could be built with liquidated damages to ensure the safe recycling. This was given further weight in the Appellate Courts decision, where it was stated that the Defendant “could, and should, have insisted on the sale to a so-called ‘green’ yard”(76)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraph 67.. This could have been done by the use of provisions in the sales agreement (MoA), where a tripartite agreement could have linked the inter-party payment to the delivery of the vessel to an approved yard. The contradictory part is here that a provision in the MoA (Clause 22) already stated that the buyer (Hsejar) had obligated itself to only sell to a shipbreaking yard which would perform the demolition “in accordance with good health and safety working practices”.(77) Ibid., paragraph 68. Unfortunately, as the Court also highlighted, such practices are entirely ignored in the shipbreaking industry, where “everyone turns a blind eye to what they know will actually happen”(78) Ibid., paragraph 69.. Thus, one may argue that the Courts indicated how the Defendant could have met their duty of care owed vis-à-vis the yard workers and thus perhaps that this is a slight indication towards a breach of the duty in case the duty would be found to exist. An interesting argument brought by the Defendant as support for not having breached the duty was that because nearly all vessels ended up in South Asia, then the Defendant was not deviating from standard practice. Here, Justice Jay was very firm in his conclusion that “if standard practice is inherently dangerous, it cannot be condoned as sound and rational even though almost everybody does the same”(79) Ibid., paragraph 15.. This argument is thus another indication that fulfilling a duty of care, if established, for a shipowner, operator or the like, will not be met just because they follow the same practice as everyone else in the industry. Unless the practice can be condoned as safe for human and environmental health, a satisfaction of a duty of care will require wider steps. Such steps may be to accept a lower sales price and thereby making sure that the sale of end-of-life vessels are recycled at safe shipyards. Another step could be to engage with the yards more directly to establish such safe practices for the long run. Some shipping companies(80) One example hereof is Maersk, see A.P. Moeller Maersk, ‘Leading Change in Ship Recycling Industry’. are very engaged in this but so far it has not resulted in any of the yards meeting the standards required to be accepted to the European List of Recycling Facilities(81) European Commission, ‘Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2020/95 of 22 January 2020 Amending Implementing Decision (EU) 2016/2323 Establishing the European List of Ship Recycling Facilities Pursuant to Regulation (EU) No 1257/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council (Text with EEA Relevance)’..

As is evident, the Courts discussed a number of facts relating to whether the Defendant could be held liable for its omission, which led to a third party exploiting the danger created. To summarise the findings and analysis hereof, it seems that some of the hurdles will be to establish that the Vessel was inherently dangerous for the exception to apply. Ultimately, the three requirements for a duty of care must also be present, and here the proximity seems to be the one most in question.

3.3.2.3 Choice of law

In this regard, the High Court briefly examined the question, and in addition whether alternatives under articles 4(82) Accordingly, the main rule is the place of the tort/delict is applicable. The exception is found in paragraph 3, where another law can be applied, if this the tort/delict is found to be more closely connected hereto., 7(83) This rule determines that for environmental damage the claim may be brought elsewhere than the starting point laid out in article 4(1) of Regulation (EC) No 864/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 July 2007 on the law applicable to non-contractual obligations (Rome II). and 26(84) The article lays down the general public policy (ordre public) exception. under the Rome II Regulation(85) Regulation (EC) No 864/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 July 2007 on the law applicable to non-contractual obligations (Rome II). would mean that other laws than those of Bangladesh would apply. In brief, the High Court held that article 4 entailed that Bangladeshi law applied, and thus the claim would be statute barred. However, they also found that pursuant to articles 7 and 26 of the Rome II, the Claimant might be able to argue that English law could apply. However, the Appellate Court was not of the same opinion as regards article 7 under Rome II. In regards to article 26, the parties’ had exchanged communication before the one-year limitation period had expired, which was evidence to the fact that the Respondent had had access to justice well before the expiration of the limitation date.(86)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev1) [2021] EWCA Civ 326 paragraph 99. However, the High Court also held that wider policy arguments could be used in support of the public policy argument.(87)Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd (Rev 1) [2020] EWHC 1846 (QB) paragraphs 85, 104. The Appellate Court did not find that the Respondent could meet the high hurdle of the public policy argument. Thus, only the argument of undue hardship would be left to state that English law should apply. On the basis of various evidence presented only before the Appellate Court, it held that the date of the Deceased’s death had been wrongly identified to the Respondent’s lawyers. This would perhaps entail undue hardship and could be decided by a preliminary hearing.